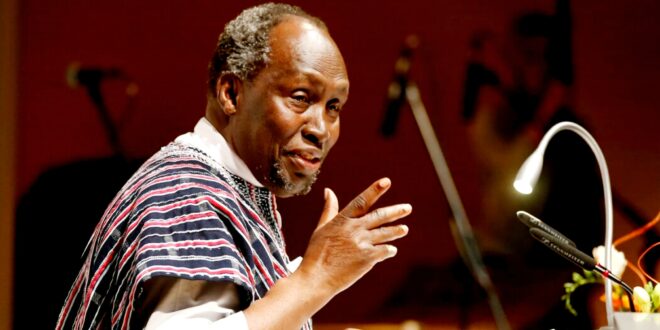

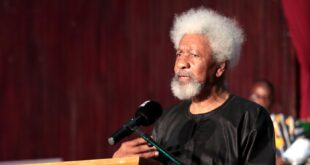

Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o passed away on 28 May. A towering figure in African literature, his works critically address colonial oppression and the unjust postcolonial order. In this tribute, Dr Pierrette Herzberger-Fofana, literary scholar and former lecturer at the University of Bayreuth, honours the life and legacy of this influential writer. A former member of the European Parliament, Dr Herzberger-Fofana personally knew Ngũgĩ and interacted with him during his time as a visiting professor at Bayreuth. She reflects on his relentless advocacy for the linguistic sovereignty of Africans and the enduring impact of his work.

![]()

Born James Githuka Ngugi on 5 January 1938, in Kamiriithu, Kenya, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o passed away on 28 May 2025, in Atlanta Georgia (USA). It is with deep sadness that I learned of his death. His daughter announced it with the following words: “He lived a full life and fought with courage.”

Ngũgĩ attended a missionary school where the language of instruction was at the beginning Gikuyu (Kikuyu). But in 1952, with the declaration of the state of emergency, English took over and Giguku was banned. School children were even slapped with a cane when they used their mother tongue in the schools.

In his major work Decolonising the Mind, he wrote: “English became more than just a language: it became THE language, before which all others had to bow respectfully.”

A life shaped by struggle

The Mau Mau uprising (1952–1960) had a direct impact on his life. While he was in boarding school, his family was sent to a detention camp. His mother was tortured and the house of his family was destroyed. His brother Gigoto, who was deaf, was shot in the back for failing to obey a British officer’s order he could not hear.

In 1959, as the British violently repressed the independence movement, Ngũgĩ went to study at Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda. In 1962, he published his first play: The Black Hermit.

A Giant of Literature

His first novel, Weep Not, Child (1964), was the first novel in English by an East African writer. Set during the Mau Mau uprising, it is told from the perspective of a 14-year-old Gikuyu boy named Njoroge. The novel, which earned a special prize at the 1966 World Festival of Black Arts in Dakar, explores the identity quest of young Africans in urban colonial societies. It is now widely regarded as a masterpiece.

Ngũgĩ exposed the scars of colonialism and social injustice. He questioned the use of a European language as a medium of education, which he saw as a denial of African identity. This question would become central to his thought.

His second novel, The River Between (1965), explores religious and cultural conflicts between two neighbouring villages. The River Honia marks the boundary between opposing beliefs and customs. The narrative deals with the controversial practice of female genital mutilation, still present today in Kenya.

In A Grain of Wheat (1967), he tells the story of Kenya’s independence through the lives of villagers preparing for Uhuru Day. The novel evokes sacrifice, betrayal and the fragile birth of national unity.

In 2022, A Grain of Wheat was selected for the “Big Jubilee Read”, a list of 70 Commonwealth books chosen to celebrate Queen Elizabeth II’s Platinum Jubilee.

Ngũgĩ’s last novel written in English was Petals of Blood, published in 1977. It’s a historical epic that condemns postcolonial corruption, neocolonial exploitation and the betrayal of revolutionary ideals. It powerfully contrasts traditional and modern ways of life.

In 1972, The magazine Times wrote: “At the age of 33, Ngũgĩ is recognised as one of Africa’s most remarkable contemporary writers.”

![]()

A Turning Point: Language and Resistance

1977 marked a turning point. James Ngũgĩ renounced his Christian name, James, and adopted the name Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, meaning “son of Thiong’o”. He declared he would no longer write in English but in his mother tongue, Gikuyu (Kikuyu).

He co-authored the play I Will Marry When I Want, performed in his village’s open-air theatre. The play, a sharp critique of class inequality and neocolonial oppression, enraged the Kenyan regime. Ngũgĩ was arrested after the presentation of his play in 1977 and imprisoned for a year without trial.

I Will Marry When I Want marked an important turning point in the author’s literary career.

In prison, he wrote Devil on the Cross in Gikuyu, on toilet paper — the first Kenyan novel in an African language. He denounced the capitalist system as a gathering of thieves and profiteers competing to be the best. The novel was banned but sold 15,000 copies.

His Prison Diary Detained documents his ordeal and his commitment.

In 1987, his novel Matigari was mistaken for a revolutionary manifesto. The government sent agents in search of the fictional character. The story, which originated in the realm of fiction, was considered real by the Kenyan authorities and ‘Matigari’ was banned. The country’s secret police transformed the literary character into a real coup leader and resurrected him as a supposed terrorist who wanted to overthrow the government. But Matigari’s only homeland is the author’s imagination, and he now shares the same fate as the author who was forced into exile.

A Fight for African Languages

Ngũgĩ was a tireless advocate for African languages. At the 1962 Makerere conference, he challenged his peers:

“How can we African writers show such weakness in defending our own languages, and such greed in claiming foreign ones, starting with those of our colonisers?”

In Decolonising the Mind, he announced : “This book is my farewell to English.”

Ngugi believed that using African languages in literature was essential to true liberation. “If you speak every language in the world but not your own, you are a slave. If you master your mother tongue and learn other languages, you are free.”

Exile and Academic Career

Persecuted for his writings, Ngũgĩ left Kenya in 1982. He lived in the UK and later in the US, where he taught at Yale, New York University and the University of California at Irvine, where he became Professor Emeritus.

In 2004, he returned to Kenya after 22 years. The next day, he and his wife were brutally attacked. His wife was raped in front of him and he was stabbed as he tried to protect her.

A Global Legacy

Ngũgĩ was a perennial candidate for the Nobel Prize in Literature, most recently in 2021, though he never received it. His works have been translated into more than 30 languages.

He received honorary doctorates from over 15 universities, among which was one from the University of Bayreuth in 2014 for “his outstanding services to the promotion of African literature, especially literature in African languages”.

The University of Bayreuth was the first university in Germany to award an honorary doctorate to the internationally renowned author. In addition, for the first time, an honorary doctorate at the University of Bayreuth was not awarded by a single faculty, but by the Graduate School for African Studies, which is anchored in all faculties. Respect, joy and congratulations came from the entire University of Bayreuth and the African partner universities.

During his two months as visiting professor at Bayreuth I was teaching there and I had the privilege to speak intensively with him. He is the great theoretician of the postcolonialism ideas.

In 2019, Ngugi received the “Erich Maria Remarque Peace Prize” in Osnabrück, Germany,

“The city of Osnabrück honours the Kenyan writer and cultural scholar with the Erich Remarque Peace Prize for his enlightening anti-colonialist themes and his reference to traditional African theatre and narrative art, as well as for his advocacy of the preservation of the mother tongue as a means of identification,” read the citation.

His book Decolonise the Mind is the basis of the award. In his acceptance speech, Ngugi said: “I was especially touched to learn that this prize honoured my advocacy for linguistic equality.”

An Immortal Voice

I fondly remember his visit to Erlangen, Germany, for the INTERLIT literary event. He gave a moving speech in Gikuyu — interpreters had to wait for the English translation before rendering it in German. It was a true lesson in linguistic dignity!

Ngũgĩ considered himself an anti-colonial writer, grounded in African culture. His body of work – novels, plays, essays, stories for children – will remain a cornerstone of world literature.

He was both rigorous and deeply human. His voice will echo through generations.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o has joined his ancestors. May he now witness the blossoming of African literature in African languages.

May you rest in peace, dear Master of African languages.

![]()

The author, Dr Pierrette Herzberger-Fofana, is a renowned literary scholar, former lecturer at the University of Bayreuth and a former member of the European Parliament. A passionate advocate for African literature, she has written extensively on post-colonial African texts, with a focus on decolonization and cultural identity. Her scholarly work and activism intersect, contributing significantly to the discourse on African literature’s role in global post-colonial narratives.

![]()

READ ALSO Dr Herzberger-Fofana awarded German city’s highest honour

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.