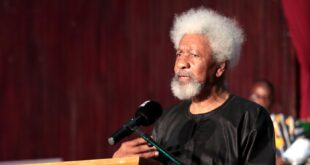

Award-winning Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie dissects the complexities of race, class and hair in her novel Americanah, writes Michael Nnaji*.

Born and bred in the Nigerian university town of Nsukka, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie already has two universally acclaimed novels, Purple Hibiscus and Half of A Yellow Sun, and the collection of short stories The Thing Around Your Neck, as well as numerous other short stories under her belt.

Americanah, which is both a derisive expression and a grudging compliment for so-called “been-tos” (those who have lived abroad), is the name of this her offering. The novel, which plays out in three countries (Britain, Nigeria and the US), examines, in the main, race and class and how they shape social interaction, for better or worse.

The heroine of the novel is Ifemelu, a confident Nigerian graduate who travels to the US in search of the proverbial Golden Fleece. She initially finds life there disconcerting and has to overcome diverse challenges, including racism. Often she is turned away from menial jobs as a waiter, bartender and cashier because of her origins and appearance.

Through the protagonist’s various challenges, Adichie seeks to weave a tale that thematises society’s various ills. Ifemelu begins a blog entitled Raceteenth or Various Observations About American Blacks (Those Formerly Known as Negroes) by a Non-American Black.

It is through her exchanges with readers, among others, that we see the true coming of age of Adichie, who applies a no-holds-barred approach, which is also exhibited when the protagonist/heroine returns home to her native Nigeria, in dealing with the country’s myriad issues. The blog exchanges are revealing and at times represent philosophical, literary and intellectual “high-watermarks” in the novel.

Further down the line, Ifemelu, who has turned into a self-styled feminist, re-unites with her childhood sweetheart, Obinze, in the commercial city of Lagos. The latter, also a university graduate, has found favour with Nigeria’s ruling class and become wealthy through property development. He is, however, mired in an unhappy marriage with a lovely child, and is initially in two minds about abandoning the marriage to hook up with his first love, Ifemelu.

As the story goes, Obinze ends up divorcing his wife and abandoning his young daughter. The act, in itself, depicts a breach of one of traditional society’s taboos, the sanctity of marriage. And on the other hand, it features perhaps the only moment where the novel appears to pander to Hollywood’s fancy for happy endings, considering the emotional torture meted out to Obinze by Ifemelu through her long silence and ostentatious dalliances with various American men during her stay in the US.

Furthermore, it reminds one that money, according to those who own it, is no magic portion for happiness, for “Obinze had begun to feel bloated about all he had acquired – the family, the houses, the cars and the bank accounts…and wanted to be freed from it all”.

This aside, the similarities of Ifemelu to the author herself have drawn suspicions of a quasi-autobiography, which Adichie has not denied. Both women studied at Princeton after schooling in Nigeria.

Another issue that comes up repeatedly in Americanah is hair: hair as viewed through the lenses of aesthetics, politics (how people are denied jobs because of their hairdo and lifestyle choices) and race/racism.

Adichie also enlightens her readers about the sophisticated and multi-layered nature of racism within America through the book’s heroine’s blog. And one passage is worth sharing: “There’s a ladder of racial hierarchy in America. White is always on top…and American Black is always on (sic) the bottom, and what’s in the middle depends on time and space (or, as that marvellous rhyme goes, if you are White, you are right; if you are Brown, stick around; if you are Black, get back!).” The intelligent humour that runs through Americanah makes it an enjoyable read.

Effectively, the book is not only about a fairy-tale love affair, hair, class and racism, but is also a clarion call to immigrants to look towards home, because that is the only place where they can be themselves. Our protagonist drives the point home as the book draws to a close and, relieved to be back home, says that “race really doesn’t really work here. I feel like I got off the plane in Lagos and stopped being black”.

* Michael Nnaji is a Berlin-based medical doctor and creative writer

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.