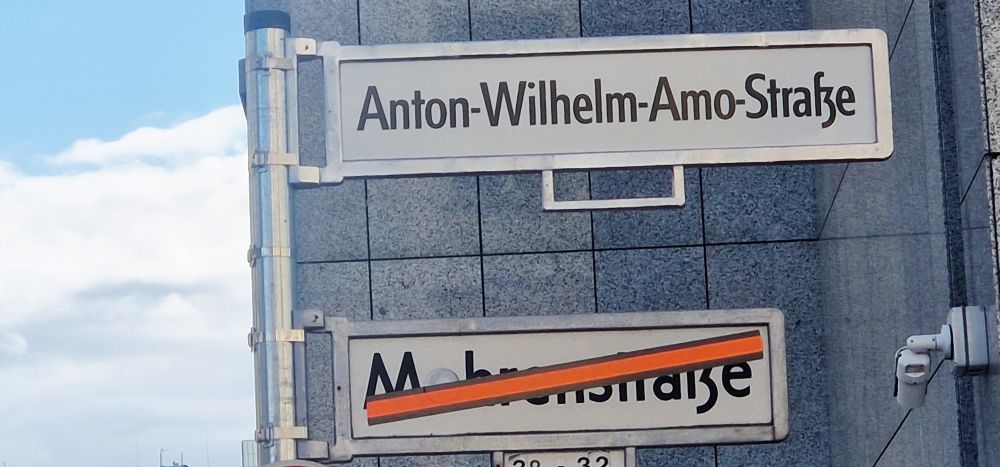

After a protracted legal battle and decades of public debate, Berlin’s Mohrenstraße in the Mitte district has officially been renamed Anton-Wilhelm-Amo-Straße. The renaming was celebrated on Saturday, 23 August, coinciding with the UNESCO International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and Its Abolition. The ceremony was only made possible after the Oberverwaltungsgericht Berlin-Brandenburg overturned a last-minute injunction granted by a lower court on 22 August, allowing the event to go ahead.

![]()

The celebration, attended by hundreds, marked the culmination of more than 30 years of agitation for the renaming of the street (defiantly referred to as M-Strasse by activists) and the U-Bahn station of the same name. It was almost derailed when opponents of the change secured a Berlin Administrative Court’s injunction on Friday to stop the official ceremony. The district administration immediately appealed, and the higher court reversed the lower court’s ruling later that evening, clearing the way for the historic moment.

![]()

The former name, dating back to around 1700, was derived from the archaic German word “Mohr”, historically used to describe Black people in a derogatory way. Over the years it had become a flashpoint in debates about racism and Germany’s colonial legacy. Critics argued the term was at best insulting and at worst deeply offensive.

Holding the ceremony on 23 August was especially significant, as the date aligns with the International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition. The day commemorates the uprising that began on the night of 22–23 August 1791 in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic), which played a crucial role in the eventual abolition of the transatlantic slave trade.

At the event, which featured speeches and music, Stefanie Remlinger, the Green Party mayor of Mitte, said the renaming represented “a necessary confrontation with Germany’s colonial past and a respectful gesture towards those impacted.” She also highlighted the long legal struggle the district faced due to continued resistance from various quarters.

Author and poet Sharon Dodua Otoo reflected on the life of Anton Wilhelm Amo, who was kidnapped as a child and brought to Europe.

Born around 1703 in present-day Ghana, Amo was likely transported to Europe by the Dutch West India Company and presented as a “human gift” to the Duke of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel. He was given the opportunity to get education and he excelled academically, becoming the first known Black academic in Germany.

![]()

In 1730, Amo earned a doctorate in philosophy, the first African to receive such a degree at a European university, and later taught at the universities of Halle, Wittenberg and Jena. His doctoral thesis, De iure Maurorum in Europa, defended the rights of Black people in Europe.

Otoo said renaming the street after Amo was especially fitting, since he not only endured racial prejudice during his time in Germany but also directly challenged European philosophical traditions of the Enlightenment. He advocated for the equality of all people and strongly critiqued slavery and racism.

Amo’s intellectual legacy has only recently begun to be rediscovered. Universities in Halle and Wittenberg are staging exhibitions about his life, Stuttgart has renamed a square in his honour and in 2020 Google dedicated a doodle to him.

![]()

Joshua Kweisi Aikins, human rights activist, political scientist and one of the earliest advocates for the name change, described the renaming as the beginning of a shift in Germany’s culture of memory. He criticized the tendency towards selective atonement for historical wrongs and called for equal recognition of all victims of past injustices.

Speaker after speaker recalled the long campaign that took the street from Mohrenstraße to Anton-Wilhelm-Amo-Straße, a struggle that began with the efforts of individuals, grew through the involvement of organizations and eventually reached institutions and policymakers. The key lesson, many emphasized, is that consistency and tenacity in pursuing just causes ultimately bring success.

Saturday marked a milestone in Berlin’s commemorative culture and its ongoing reckoning with its colonial legacy. Recognition is due to organizations such as Decolonize Berlin, Initiative Schwarze Menschen in Deutschland, Each One Teach One and many others whose tireless work made this epochal event possible.

Femi Awoniyi

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.