A growing number of nations are successfully reclaiming their cultural heritage, but advocates say former colonial powers like the UK and France must do more.

A wave of restitution is moving across Europe, as former colonial powers begin returning looted artefacts and human remains to their countries of origin, according to a recent review by the Berlin-based advocacy group Colonialism Reparation. However, the group insists that these actions, while welcome, are only a first step and that major holders like the United Kingdom and France continue to lag behind.

The push for the repatriation of cultural treasures stolen during the colonial era is gaining unprecedented momentum. The Netherlands, Germany and Belgium have all taken significant, concrete steps in recent years to address historical injustices.

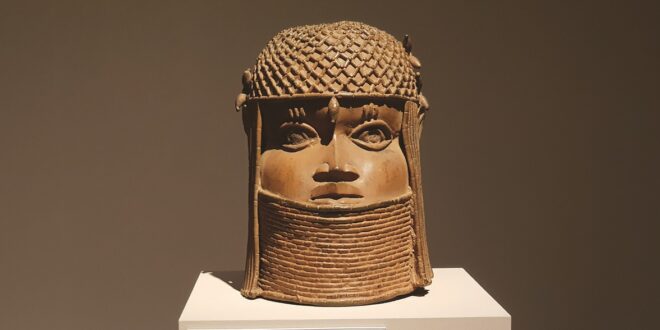

The Netherlands has been particularly active, establishing formal guidelines for restitution. This has led to the return of hundreds of objects to Indonesia and Sri Lanka in 2023 and 2024, with a further 119 prized Benin Bronzes repatriated to Nigeria in 2025.

Similarly, Germany, following a landmark joint declaration on the Benin Bronzes, has returned an initial batch of 22 objects to Nigeria. It has also repatriated the remains of more than 100 Māori and Moriori ancestors to New Zealand. A “first wave” of Cameroonian cultural heritage is expected to be returned in September 2025.

In Belgium, a 2022 law has enabled the Royal Museum of Central Africa to begin the monumental task of cataloguing its collection of approximately 84,000 objects, predominantly from the Democratic Republic of Congo. The inventory is now publicly accessible online, a move seen as a precursor to their eventual restitution.

“This is an inevitable passage of human evolution,” stated Colonialism Reparation. “The repatriation of remains and the definitive restitution of looted treasures is the necessary first step towards the broader reparation of the damages of colonialism.”

The advocacy group notes that requests are coming not just from African nations but also from countries across Asia and South America — including Algeria, Angola, Egypt, Ethiopia, Nigeria, South Africa and Zimbabwe. The African Union and even the United Nations figure in those calling for restitution.

This global shift highlights the slow progress of some major former colonial powers. France, despite high-profile promises, has returned only a fraction of the tens of thousands of looted treasures in its museums. Advocates hope it may soon be forced to approve a framework law to facilitate further restitutions.

The United Kingdom, however, is singled out for its continued resistance. “The UK is resisting to the bitter end,” the press release notes, “despite its enormous responsibilities, denying the evidence and remaining deaf to requests.” Institutions like the British Museum, which holds a vast collection of contested artefacts, remain at the centre of the debate.

Colonialism Reparation is calling on all former colonizers — including the UK, France, Germany, Spain, Portugal and Italy — to stop hindering the process and to engage meaningfully in the repatriation and restitution of cultural property as a fundamental act of historical justice.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.