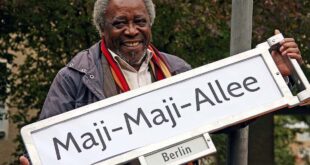

Céphas Kosi Olatidoye Bansah, the Togbe Ngoryifia of the Hohoe Gbi Traditional Area, Ghana, has been living in Germany since 1970. After he was named chief of the 300,000-strong community of Ewe-speaking people in 1992, Bansah chose to continue living in Germany instead of returning home.

The master agricultural machinery mechanic and master motor vehicle mechanic, who is better known in Germany as König Bansah, thus reigns as a part-time monarch while running his auto workshop in the city of Ludwigshafen full-time.

His story simply fascinates – a hardworking auto workshop operator in Germany and at the same time a traditional chief in faraway Africa! König Bansah, admired by many Germans for his openness, is therefore regularly featured in the news media in the country. Dressed in all his royal finery, he is also a frequent guest at major events such as folk’s festivals and cultural or entertainment functions.

In October, the city of Bad Dürkheim, the heartland of the wine-producing region of southwest Germany named Togbe Céphas Bansah as the Golden Winemaker 2022. He joins the list of eminent personalities in Germany who have received the award in the past, including former Chancellor Helmut Kohl. Bansah had also made history in 1999 when he was crowned the first wine king in German history, helping to revive a dying tradition.

Leveraging on his visibility and the goodwill he enjoys in the German population, he raises funds for the implementation of humanitarian and development projects in his home region in Ghana.

Here’s an exclusive interview with the 72-year-old master technician, traditional chief and philanthropist. König Bansah talks about how it was when he came to Germany, his chieftaincy title and how it has changed his life, his philanthropic activities, among other issues, and he offers a golden advice to Africans living in Germany.

—–

You came to Germany in 1970. Why Germany and not Great Britain? Didn’t the language put you off?

Yes, I came to Germany in 1970. I was just 22 years old and had just finished technical school in Togo. My parents had always wanted one of their children to go to Germany to learn something from the Germans, who were considered role models. But the deciding factor was my grandfather, who was a king. He grew up at a time when our region [the Volta region of Ghana] was part of the German colony of Togoland. He himself had experienced how the Germans taught the inhabitants various trades, and he always talked to us, the children, about them.

How did you then find yourself in Germany?

It was in my last school year in Togo when the opportunity finally presented itself – an international exchange programme from Bonn-Bad Godesberg was offered. My teacher, Mr Schmitt, recommended me for it. I diligently wrote applications – all in German – to get a training position as a technician or mechanic in Germany.

And so it happened that in late 1970 I came to Germany to start my training, with only a basic knowledge of German.

How did you feel when you were leaving your country?

I knew that a whole new phase of my life was beginning, full of opportunities – I had not thought of problems at all at first.

The whole Bansah family took me to the airport in Accra, it was a sad farewell, especially for my mother. However, I was full of energy and wanted to get to know the world that was so new to me as quickly as possible. For the first time in my life, I boarded a plane, I flew to Frankfurt with Deutsche Lufthansa.

What were your first impressions of Germany?

The adventure in Germany began immediately I landed in Frankfurt early the next morning. I had been impressed by Kotoka Airport in Accra, now I was completely blown away by Frankfurt International Airport. I couldn’t take my eyes off the huge arrival hall, the very high ceilings supported only by a few steel girders. How could something like that stand? I thought.

How was life in Germany at the beginning? The weather, the people? The food?

My company had rented a room for me in a Catholic youth hostel, my new home for the next few months. I felt terribly cold in the first night, although it was only September and there was no ice falling from the sky yet, which my mother had always warned me about. But I was compensated by the warmth of my new colleagues and the family of the owner of a large agricultural machinery company where I worked.

I quickly made friends with them, but also with my classmates at the vocational school that I attended.

On weekends, I helped out on their farms, with the harvest, the grape harvest, or repairs. This way I quickly learned the language and was also provided with homemade bread and sausage as well as the vegetables the families grew.

But as much as I liked sauerkraut and bratwurst, I missed my food from Ghana so much. In my first own flat, I could finally cook for myself – meat and vegetables in hot sauce. In the 70s, you couldn’t buy yams, cassava or plantains here yet. I often invited my German friends over for dinner and they loved it.

Did you have contact with other Africans back then?

There were very few Africans in my area, around Ludwigshafen; probably some students in Mannheim, I only knew one young man from Benin.

You were a boxer and even once a district flyweight champion. What role did sports play in your integration?

A friend took me to boxing training one day. I enjoyed it because I had always liked sports. The trainer recognised that I had talent and packed a punch, despite my weight of only 42 kg. So, I trained regularly, took part in competitions and made it to Southwest Champion in flyweight in 1975. Besides physical fitness, sports was my leisure activity and I got to know new people. And that was very important for me, since I lived here without a family.

What made you decide to open a car repair shop in Ludwigshafen and not in your home country after your training?

I learnt a lot in Germany, received master craftsman’s certificates in two trades, but it wasn’t enough for me. I wanted to learn more, and by setting up my own business in Germany, I could also prove my competence to the Germans. I trained apprentices, all Germans. My German customers brought their vehicles to me for repairs because they trusted me.

You are well-known and popular in German society. How did you do it?

People were very nice to me when I came to Germany as a young man. So, I was also able to return this warmth. My initial concerns about how I would be received as a Black person in an all-White country faded after a short time. I respected them – also for their expertise. And the more I learned, the more I was respected. Hence, mutual respect is number 1 for me.

You have lived in the Palatinate since your arrival in Germany. What is special about the region for you?

The region around Ludwigshafen has become my second home, I have friends here, my family is here, I speak the local dialect, I like the regional festivals. I’ve had success here, why should I have left and started all over again in another region? And by the way, the Palatinate is very scenic and has a pleasant climate.

Many Africans return to their home countries in old age. But you continue to live between the two worlds. Why?

When I was named king, I promised to strive to improve the living conditions of the people, and I could only do that then, like today, from Germany. Only from here can I initiate and, above all, finance my aid campaigns. So, I still live between two worlds, between the crown and the spanner, so to speak. And that is exactly the title of my book (Zwischen Krone und Schraubenschlüssel), which I co-wrote with my wife.

Students are trained there to become nurses and midwives/Photo: Céphas Bansah

How did you become a chief? How has this development changed your life?

My grandfather was a king, but that one day I would be elected Togbe Ngoryifia of Gbi Traditional Area in Hohoe by the elders, did not cross my mind. I had built my life in Germany and founded my family. This decision, which I have never regretted, had a decisive influence on my life. Suddenly I felt responsible not only for my family, but for thousands of people. And these people had expectations of me.

You are actively involved in the development of your home region. How satisfied are you with the result?

The people in my home region walk every day over the bridges I have built for them. No long detours, no life-threatening crossings of rivers. They drink clean water from the boreholes in their villages, are healthier and don’t have to carry water over many kilometres. The children go to modern schools and one or two patients have recovered thanks to the help from Germany. Even the women and young people who are housed in the newly-built police cells through my efforts are happy.

Black people complain about racism in Germany. What do you think is the best way to fight racism in society?

Personally, I think the only way to do that is to educate Europeans more about Africa. In Europe, you don’t learn much about our real history, and nothing about Africa’s contemporary reality. And if they do, it’s only from the European perspective.

The knowledge of the value of African culture and its positive influences on Europe has always been suppressed. If the Europeans understand that we Africans have an equal value system, really get to know us, then they will not be afraid of us. Because fear and ignorance lead to racism.

Looking back, what advice would you give Africans for a successful life in Germany?

I adjusted my life to the mentality of the Germans, live among them, but have never forgotten where I come from. I am very proud to be Ghanaian. In the 1970s, the differences between Ghana and Germany, for example, in the fields of science and technology, were great, and I wanted to learn, but it was clear to me that one generation was not enough to catch up as an African. That is why it should be important for every African to send their children growing up in Germany to good schools. The young generation, raised with an African and German soul, can be very successful in Germany. I can see it in my children; my son Carlo is the managing director of the Vorderpfalz district association of the German Red Cross, and my daughter Katharina is a successful graphic designer.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.